You will hardly find another word that is used with less care than ‘strategy’. Strategies are variably described as the ‘course of action for the future’, a ‘pattern, a behaviour that is constant over time’, a method for achieving a ‘unique new position a business seeks to take up’, or a ‘bundle of guidelines for dealing with a particular situation’. Strategies are defined as ‘a regularity within the stream of decisions’, the ‘planned evolution’ of a business, or as a ‘plan for integrating the central goals, guidelines, and actions into a coherent whole’.[1]

Because the term suggests a relation to the future, ‘strategy’ is frequently used when something is meant to be seen as crucial to success. ‘Strategic procurement management’ sounds much more impressive than ‘simple procurement management’, ‘strategic personnel management’ adds a special note to the hiring and firing of people because its meaning seems to take the future into account, and the phrase ‘strategic advice’ promises higher daily rates for consultants compared to the offer of good old ‘organizational advice’. The adjective ‘strategic’ appears to be combinable with practically every noun used in management theory; it signals importance without it being clear at all how it would change the meaning of the noun if the adjective were simply dropped.

From the perspective of systems theory, strategy denotes the search process looking for means that are suitable for achieving a previously defined purpose. Strategy formulation (or strategy development) would thus be the search process for finding suitable means.[2] Strategy implementation would be the process of using the means that have been identified as suitable for achieving the previously defined purpose. Strategy formation would be the means which emerge in the shadow, so to speak, of the official search process that aims at achieving the purpose.

Only once we have given the word ‘strategy’ a precise definition in this way can the debate over strategy be linked up with the discussion on purposes and means in organizations that is so important in organization studies. By purposes – or goals – organization studies means a clearly defined state that is to be reached. By means, it understands the possible pathways that lead to this state. If purposes are meant to guide the search for means – that is, if they are to bring about structural effects in an organization – they need to be specified to such a degree that it becomes possible to say unambiguously whether they have been achieved or not. For that to be the case, the substance of the purpose (what is to be achieved?), the extent (how much of it is to be achieved?), the temporal dimension (by when is it to be achieved?), the personnel aspect (who is responsible for achieving the purpose?), and the spatial aspect (where is it to be achieved?) all need to be specified.

In the classical understanding of strategy, the specification of the mission – the long-term goal – of an organization stands at the beginning of the process. Based on an analysis of the organization’s environment, its internal capacities, and the available resources, the next step is to determine the various means for achieving the overall purpose. Then follows an extensive analysis of the available options regarding their possibilities and risks before a strategy is finally selected that promises to secure that the long-term goal is achieved. Thereafter, the selected strategy is operationalized. Quantitative targets are established, milestones defined, and action plans drawn up, with management monitoring that these are being adhered to.

This classical understanding, which is represented by the so-called design school or planning school, is based on an understanding of organizations that is labelled purpose fetishism in organization studies. The whole organization is constructed on the basis of a main purpose at the top that is to be achieved. Then the means for achieving it are defined. These means become subordinate purposes for which, in turn, the means for achieving them need to be established. The result is a pyramid-shaped structure of superior and subordinate purposes that can be used to determine the usefulness of each and every action in the organization. In short, the intention is the construction of a ‘strategy-focused organization’.[3]

The structural idea of an organization that informs this means-end logic is actually an old one. Fritz Nordsieck, one of the founders of German business economics, was of the opinion that the task to be fulfilled by an organization should be the ‘point of departure’ for the determination of its structure. The task, Nordsieck said, should be systematically divided up into sub-tasks, and these should then be allocated to specific units, or even better specific divisions , in the organization. The interlocking of the achieved sub-tasks should then lead to the achievement of the overall task.[4]

This model requires that there be no contradictory purposes or sub-purposes in an organization. If that were the case, the fulfilment of the sub-tasks would not add up to the fulfilment of the overall task. The contradictions would lead to irritations and problems in the early planning stages but in particular when it comes to developing a coherent strategy.

This way of proceeding on the basis of purposive rationality needs to draw a strict line between the development and the implementation of strategies. The idea is that first a strategy needs to be formulated before one can think of implementing it. This conception resembles a coldly calculating military strategist who, together with his General Staff, thinks of a tactic and then gives out the corresponding orders to the fighters at the front. In this case, military discipline guarantees that the orders are followed and the ‘actual carrying-out’ is therefore ‘relatively unproblematic’.[5]

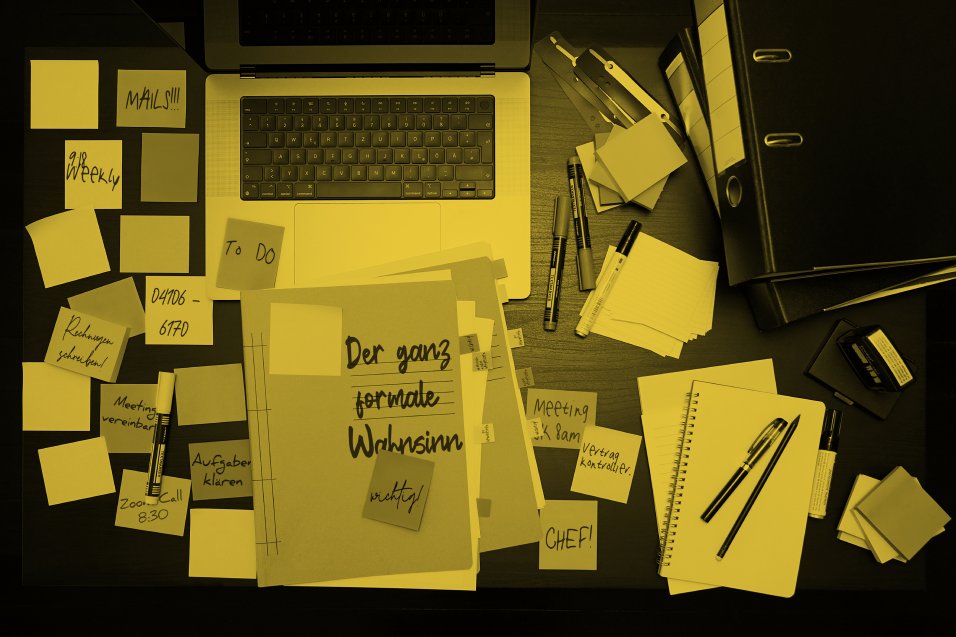

In reality, this way of proceeding often produces strategic masterplans that run to hundreds of pages, listing precise targets, schedules, and budget allocations. These masterplans describe sub-targets in minute detail, all of which are expected to be ‘smart’, that is, specific, measurable, accepted, realistic, and with clear deadlines. The schedules sometimes stipulate precise deadlines to the day, sometimes even to the hour, for hundreds of these sub-targets. And for the achievement of each of these sub-targets a budget is determined to the Dollar, Euro, or Renminbi. The strategic plans then only need to be made available to the employees and compliance with them be overseen by the management.

The limits of classical strategy management find expression in the complaints about the ‘implementation gap’. The gap that remains at the end of a strategic process, and that is often overlooked, is not caused by a lack of commitment among the top management, or by the middle management’s insufficient professional expertise regarding implementation processes, or by inadequate consultants; rather it is the inevitable outcome of the narrow perspective based on purposive rationality that informed the strategy process.

There is by now broad agreement in organization studies that the idea of deriving sub-purposes harmoniously from a shared main purpose is no more than a fantasy indulged in by the top management. In truth, organizations are characterized by competing purposes, a regular twisting of means-ends relations, purposes that are only window-dressing, the arbitrary and unobserved substitution of purposes, and sub-purposes that take on a life of their own.[6] When developing a strategy for an organization, these factors should not be seen as pathologies of an organization; instead, the strategy to be created must be adapted to these phenomena.

With this in mind, it is understandable why suggestions have been produced for fundamentally different procedures when designing strategy processes. Approaches such as ‘logical incrementalism’, ‘learning strategy development’, the ‘grassroots model of strategy formation’, ‘discursive strategy design’, or ‘effectuation’ differ in detail, but at their core they all abandon the understanding of organizations as based on purposive rationality that informs classical strategy theory. These approaches can therefore only be understood and contextualized against the critique of purposive rationality in organization theory.

[1] Stefan Kühl, Strategien entwickeln: Eine kurze organisationstheoretisch informierte Handreichung, Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2016.

[2] See the early publication by Georg Schreyögg, Unternehmensstrategie: Grundfrage einer Theorie strategischer Unternehmensführung, Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, 1984, p. 246.

[3] See for example Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton, The Strategy-Focused Organization: How Balanced Scorecard Companies Thrive in the New Business Environment, Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2001, pp. 2ff.

[4] Fritz Nordsieck, Die schaubildliche Erfassung und Untersuchung der Betriebsorganisation, Stuttgart: Metzler, 1932, p. 10.

[5] Thus the image presented by Richard Whittington, What is Strategy and Does It Matter?, London and New York: Routledge, 1993, p. 17.

[6] This was already pointed out by Niklas Luhmann in his Zweckbegriff und Systemrationalität, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1973.